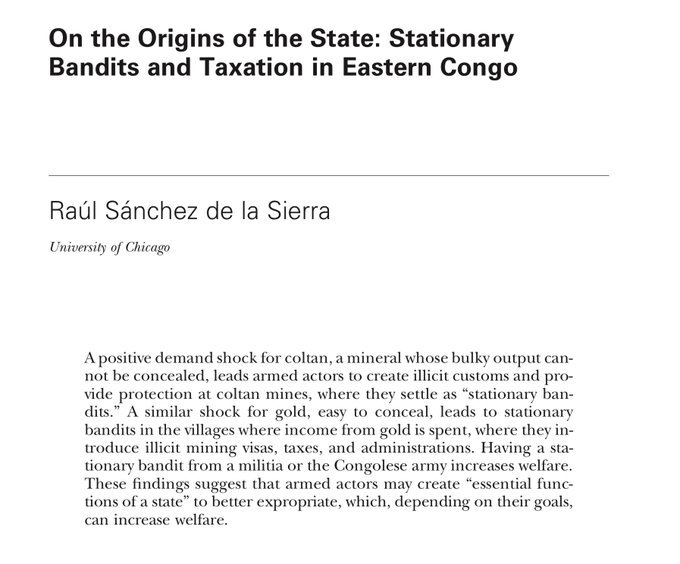

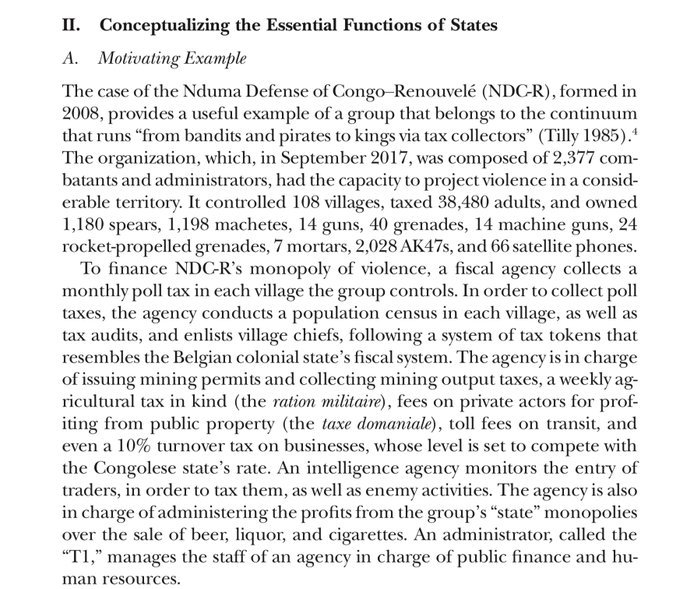

The “stationary bandit” view of the state derives from Mancur Olson. In the state of anarchy, some people are bandits who profit by stealing from others. This theft prevents people from increasing output, though. It is profitable for the bandit to settle down and impose taxes. By guarding their population from other bandits, it is possible for both bandits and peasantry to be better off off. This theory makes several predictions. First, since forming the apparatus of a state entails paying fixed costs, we should have more states when there is a positive income shock. Second, the form the state takes should be influenced by what is easiest to tax. The Democratic Republic of Congo provides the ideal place to test this. Public order broke down, especially in the east. There are still many competing militias, of which the Nduma Defense of Congo-Renouvelé is a representative example.

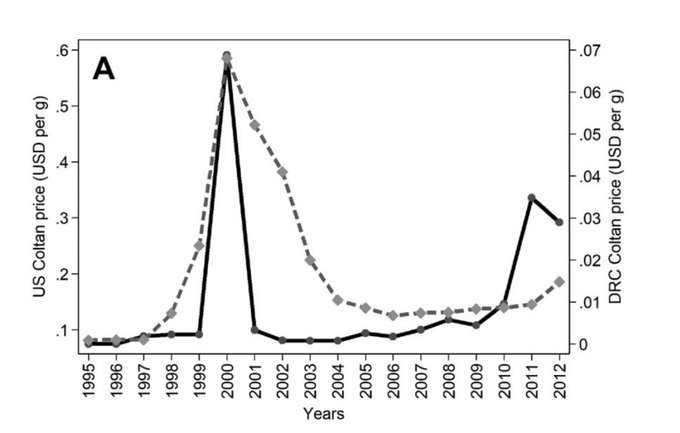

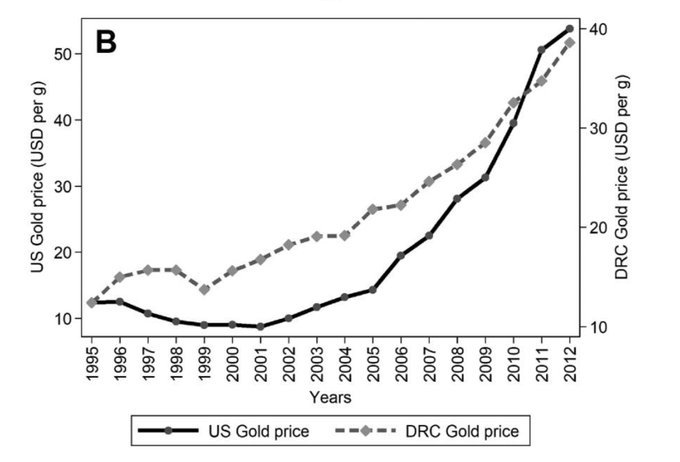

There are two primary sources of economic activity — coltan and gold. While both of these are sources of mineral wealth, they imply very different things for the organization of the state. Coltan, which is hard to conceal, necessitates taxing production. Armed militias find it cheapest to tax by requiring the purchase of licenses by miners. Gold, which is easy to conceal, necessitates taxing the consumption of the people. This implies very different things for state capacity — to legitimately impose consumption taxes. The militias have to provide public goods, like law and order. Not so for production taxes. There, the state extracts surplus, but without providing anything in return. Prices for coltan surged with the introduction of the Playstation II (and flopped when it failed); gold surged after the Great Recession. In both cases, state formation greatly increased, but only in the areas endowed with those minerals.

It is the external forces who, lacking a tie to the people, engage in arbitrary killings and theft.