Bibliography to add

- Joseph Ward Swain, “The Theory of the Four Monarchies: Opposition History under the Roman Empire,” cp 25 (1940): 1–21; and Samuel K. Eddy, The King is Dead: Studies in the Near Eastern Resistance to Hellenism 334–31 BC (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1961). On the construction of time and history in the Seleucid era, see now Paul J. Kosmin, Time and Its Adversaries in the Seleucid Empire (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2019). The classic study of the four kingdom schema in Daniel remains Reinhard G. Kratz, Translatio imperii: Untersuchungen zu den aramäischen Danielzählungen und ihrem theologiegeschich tlichen Umfeld, wmant 63 (Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirchener, 1991). Dated but still valuable is David Flusser, “The Four Empires in the Fourth Sibyl and the Book of Daniel,” ios 2 (1972): 148–75.

Context

Basically in Daniel 2 you have 4 statues symbolized as world empires that dominate history. Represented by the head of gold, explicitly identified as King Nebuchadnezzar’s empire (Daniel 2:37–38). Depicted as the chest and arms of silver, an inferior kingdom that succeeded Babylon (Daniel 2:39; Medo-Persia). Symbolized by the belly and thighs of bronze, a kingdom that ruled over much of the known world under Alexander the Great (Daniel 2:39). Represented by legs of iron and feet partly of iron and clay, a strong but divided kingdom (Daniel 2:40-43) which one is this? In Daniel 7 you have the 4 beasts. A lion with eagle’s wings, symbolizing Nebuchadnezzar’s reign (Daniel 7:4). A bear raised on one side, with three ribs in its mouth, indicating its conquest of Babylon and dominance (Daniel 7:5). A leopard with four wings and four heads, representing Alexander’s swift conquests and the division of his empire among four generals (Daniel 7:6). A terrifying beast with iron teeth and ten horns, symbolizing its strength and eventual fragmentation into smaller kingdoms (Daniel 7:7–8).

Who’s the 4th kingdom?

The fourth kingdom in the biblical Book of Daniel is never explicitly named but is identified symbolically. In chapter 2, it is represented by the iron legs of a giant statue. In chapter 7, it is depicted as the most terrible hybrid beast with iron teeth. Initially, for the intended audience of the Book of Daniel during the Maccabean Revolt (167–164 BCE), the fourth and final kingdom was understood to be the oppressive Seleucid Empire.

This identification is rein forced elsewhere by allusions to the hated Antiochus (Cf. Dan 7:8, 24b–26; 8:9–12, 23–25; 9:26–27; and 11:21–39), including a skeleton version of the schema in chapter 8 (in which all the kingdoms but the first are named) (Dan 8:20–21a) and the introduction of a different schema of “seventy weeks” in chapter 9 (Cana Werman, “Epochs and End-Time: The 490-Year Scheme in Second Temple Literature,” dsd 13 (2006): 229–55).

However, for Prof. Segal, the fourth kingdom in the four kingdoms motif as presented in the Book of Daniel is understood to be the Hellenistic Empire (Greece).

- The four kingdoms dream in Daniel chapter 2 and the vision in chapter 7 both begin with the Babylonian kingdom and extend historically to the Hellenistic empire.

- According to Michael Segal in “The Four Kingdoms and Other Chronological Conceptions in the Book of Daniel,” the primary interest of the authors of these apocalypses lay in their contemporary condition, which was the Greek (Hellenistic) empire.

- The progression in Daniel 2 and 7 shows a succession of empires leading up to the establishment of a heavenly kingdom that will replace the earthly ones. The fourth of these earthly kingdoms is understood to be the Hellenistic empire, which was the dominant power at the time of the composition of these sections of Daniel.

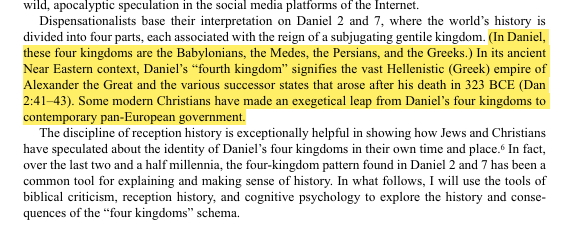

According to the book of Daniel itself, the four kingdoms are the Babylonians, the Medes, the Persians, and the Greeks. Daniel 2 specifically updates the Persian three-kingdom schema by adding a fourth slot that references the Hellenistic empire.

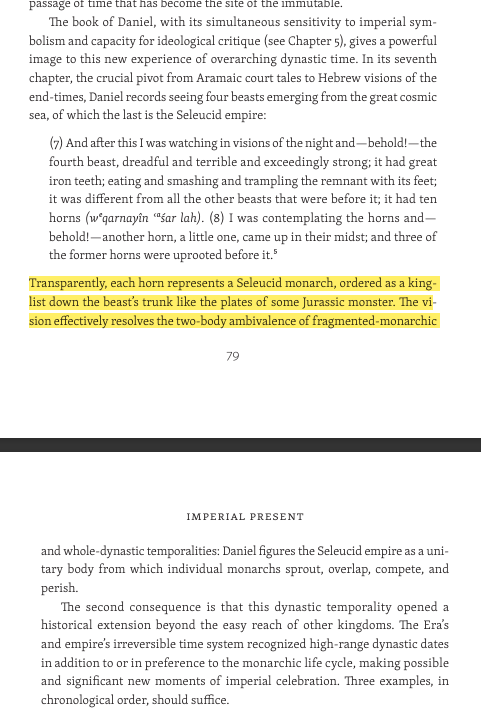

The fourth kingdom in the Book of Daniel is understood to represent the Macedonian empire, which subsequently fractured into the Seleucid and Ptolemaic kingdoms. Specifically, in Daniel’s vision of the four beasts in chapter 7, the fourth beast, described as dreadful, terrible, exceedingly strong, and different from the others, with ten horns, symbolizes the Seleucid empire.

The eleventh horn that arises later is often interpreted as Antiochus IV Epiphanes. The chosen kingdom in the Book of Daniel is the everlasting kingdom that God will set up, which will never be destroyed or left to another people. This kingdom is prophesied to replace the succession of earthly empires. “one like a son of man” who approaches the Ancient of Days and is given “dominion and glory and kingdom…His dominion is an everlasting dominion…and his kingdom is indestructible”. It’s an eschatological reality that will follow the era of gentile monarchies, including the Seleucid empire

Why the Fourth Kingdom Isn’t Just the Initial “Greek Kingdom” & Why the Chosen Kingdom Isn’t the “Greek Kingdom” (or any earthly kingdom):

- The “chosen kingdom” in Daniel is explicitly stated to be established by “the God of heaven”. It is not a kingdom that arises through human conquest or succession, like the Babylonian, Median, Persian, or Macedonian/Seleucid empires.

- This kingdom is characterized by its eternal and indestructible nature. Daniel 2 states it “will never be destroyed, nor will it be left to another people…but it will itself endure forever”. Similarly, Daniel 7 describes its dominion as “an everlasting dominion, which will not pass away, and his kingdom is indestructible”.

- The chosen kingdom is prophesied to replace the succession of human empires. In Daniel 2, the stone strikes the statue representing the four kingdoms, crushing them and growing into a great mountain that fills the whole earth.

- For why it isn’t specifically the 4th kingdom:

- chapters 7 and 8 depict a succession of empires. Alexander the Great’s kingdom breaks apart after his death into multiple successor kingdoms. Daniel 8 describes the great horn of the he-goat (Alexander) being broken and replaced by four conspicuous horns, which represent these successor kingdoms (page 143). These are the Seleucid and Ptolemaic empires (page 144).

- Daniel 11 further clarifies this by detailing the interactions between the “king of the south” (Ptolemy I) and one of his princes who becomes strong (Seleucus I), establishing the separate origins of the Seleucid empire from Alexander’s initial conquests.

Daniel’s Four Kingdoms in the Syriac Tradition

The predominant historical interpretation within the Syriac tradition identified the fourth kingdom in the book of Daniel as the Greeks, specifically the successors of Alexander the Great. This “Greek interpretation” is notably different from the “Roman interpretation” that was more common among early Jews and Christians, who saw the fourth kingdom as the Roman Empire.

This Greek interpretation is evidenced in several Syriac sources:

- Headings and additions in the Peshitta manuscripts of Daniel (dating from the 6th century onwards for chapters 7-8, and 10th century onwards for chapter 11) include rubrics like “Darius the Mede” and “Death of Alexander, the son of Philip,” and additions referring to “Alexander the First, the son of Philip”.

- Pseudo-Ephrem’s commentary on Daniel in the Catena Severi (9th century?).

- The commentaries by Ishodad (9th century) and Bar Hebraeus (13th century).

- The Syriac Alexander Legend (629/30), the Alexander Poem (between 630 and 640?), and the Apocalypse of Pseudo-Methodius (691/692 AD).

- See Botha, ‘he Reception of Daniel Chapter 2’; idem, ‘he Relevance of the Book of Daniel in Fourth-Century Christianity according to the Commentary Ascribed to Ephrem the Syrian’, in Katharina Bracht and David S. du Toit (eds.), Die Geschichte der Daniel-Auslegung in Judentum, Christentum und Islam: Studien zur Kommen-tierung des Danielbuches in Literatur und Kunst (BZAW 371; Berlin–New York, 2007), pp. 99–122. We disagree with Botha regarding the attribution of this commentary to Ephrem ‘or one of his students’; cf. Bas ter Haar Romeny, ‘Ephrem and Jacob of Edessa in the Commentary of the Monk Severus’, in George A. Kiraz (ed.), Malphono w-Rabo d-Malphone: Studies in Honor of Sebastian P. Brock (Gorgias Eastern Christian Studies 3; Piscataway, NJ, 2008), pp. 535–557; idem, ‘he Peshitta of Isaiah: Evidence from the Syriac Fathers’, in W.h. van Peursen and R.B. ter Haar Romeny (eds.), Text, Translation, and Tradition: Studies on the Peshitta and its Use in the Syriac Tradition

- Cf. Reinink, ‘Alexander the Great’, p. 162; idem, ‘Die Entstehung der syrischen Alexanderlegende als politisch-religiöse Propagandaschrit für Herakleios’ Kirchen-politik’, in C. Laga, J.A. Munitiz, and L. Van Rompay (eds.), Ater Chalcedon: Studies in heology and Church History Ofered to Professor Albert van Roey for his Seventieth Birthday (OLA 18; Leuven, 1985), pp. 263–181, esp. 273, 276 (= idem, Syriac Chris-tianity, III). Gerhard Podskalsky, Byzantinische Reichseschatologie: Die Periodisierung der Weltgeschichte in den vier Grossreichen (Daniel 2 und 7) und dem Tausenjährigen Friedensreiche (Apok. 20): Eine Motivgeschichtlichte Untersuchung (Münchener Uni-versitäts-Schriten. Reihe der philosopischen Fakultät 9; München, 1972), pp. 16–19. Cosmas considered Rome as the 4th kingdom, see below. Cf. Reinink, ‘Alexander the Great’, p. 162; idem, ‘Die Entstehung der syrischen Alexanderlegende als politisch-religiöse Propagandaschrit für Herakleios’ Kirchen-politik’, in C. Laga, J.A. Munitiz, and L. Van Rompay (eds.), Ater Chalcedon: Studies in heology and Church History Ofered to Professor Albert van Roey for his Seventieth Birthday (OLA 18; Leuven, 1985), pp. 263–181, esp. 273, 276 (= idem, Syriac Chris-tianity, III).

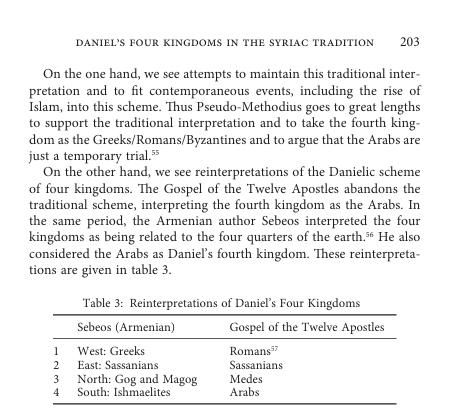

However, the Syriac tradition also saw reinterpretations of the fourth kingdom in response to historical events, particularly the rise of Islam in the 7th century:

- Facing the permanence of the Arab conquests, some Syriac apocalyptic texts identified the Arabs as Daniel’s fourth and final kingdom. The Gospel of the Twelve Apostles (694 AD?) is a prime example of this radical shift, where the author no longer considered Arab rule as a temporary event.

- Other responses, like that of Pseudo-Methodius, attempted to maintain the traditional interpretation of the fourth kingdom as Greek/Roman/Byzantine and viewed the Arab conquests as a temporary trial

- The Armenian author Sebeos, in the same period, also interpreted the Arabs as Daniel’s fourth kingdom, linking the four kingdoms to the four quarters of the earth.

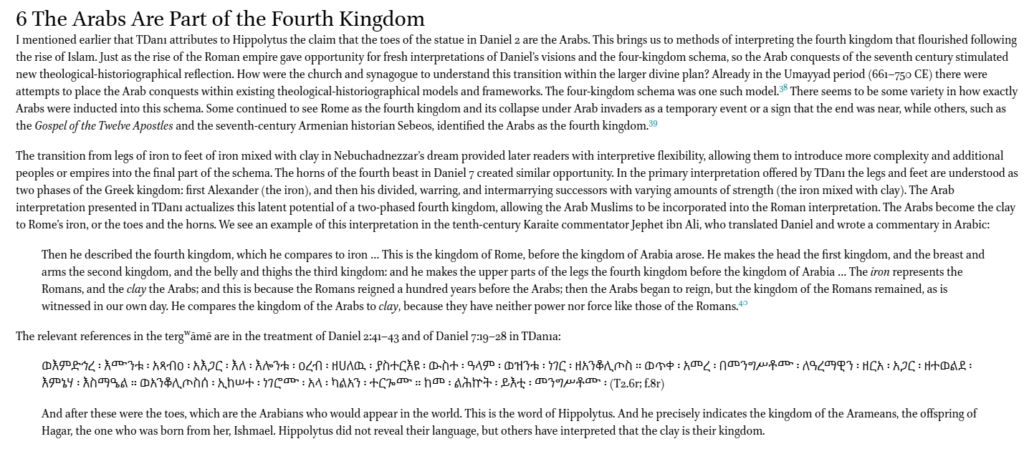

The Arabs Are Part of the Fourth Kingdom

Roman Interpretation

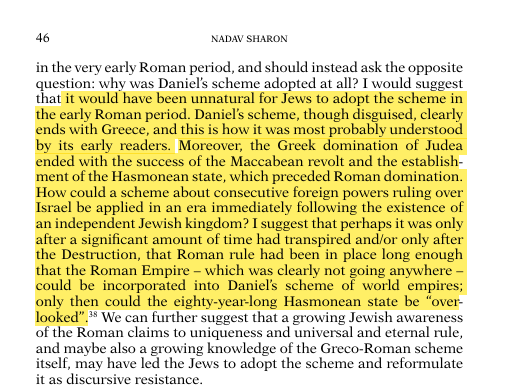

The Book of Daniel, likely understood by its early readers, presented a sequence of four foreign powers ruling over Israel, with Greece as the fourth and final empire before the establishment of God’s eternal kingdom, often interpreted as a period of Jewish sovereignty. The empires in Daniel are not explicitly named, although later Jewish tradition identified them as Babylon, Media, Persia, and Greece.

With the rise of the Roman Empire and its conquest of Judea, the original Danielic scheme, which ended with Greece, no longer aligned with the current political reality for Jewish communities. So they had to reinterpret it as Rome. In pre-rabbinic Jewish texts and later rabbinic literature, the four-empires scheme was reapplied, with Rome taking the place of Greece as the fourth empire. In his Jewish Antiquities, Josephus retells Daniel’s vision of the statue, implicitly identifying the fourth, iron empire as Rome, and while he doesn’t explicitly mention the subsequent stone (symbolizing the Jewish kingdom), he directs curious readers to the Book of Daniel, thus hinting at Rome’s eventual fall and a future Jewish empire.

Fourth Sibylline Oracle prophesizes the rise and fall of Assyrian, Median, Persian, and Macedonian empires, followed by a fifth empire – Rome – which will eventually face divine retribution for its treatment of the Jews. Although it presents Rome as the fifth empire in the Greco-Roman sense, it casts its future destruction as divinely ordained prophecy, undermining its claim to eternity